When the first women graduated from the enlisted infantry course in November 2013, I was exuberant. Deployed to Afghanistan at the time, I remember adding this to my list of updates for our morning staff meeting. None of the men at the staff meeting seemed as excited as I was. Perhaps I should not have been surprised.

As a historian, I knew the patterns of gender integration.

- Conflict created an expanded need for women’s service.

- Women performed well in their new roles.

- Congress and the Defense Secretary moved to make women’s opportunities permanent.

- The services resisted.

- Congress and the Defense Secretary mandated women’s opportunities.

- Some women walked through those newly opened doors and did well.

That day in November 2013, I thought I was witnessing Step 6. Women had proven they could complete the course. For the male Marines who completed the course, that was all that was necessary. After graduation, they proceeded directly to their infantry units.

In my excitement, I severely underestimated something. You see, for all the years I had been in the Marine Corps, the primary thing that mattered was being a good Marine and a good leader. As long as I maintained that standard – which included mental and physical toughness, grit, resilience, determination, critical thinking skills, leadership skills, integrity and professionalism – everyone treated me like I belonged. Everyone treated me with respect. Everyone treated me like a Marine.

I always had a seat at the table. I always felt I could speak up when I had an idea or questioned a plan. My seniors placed me in leadership roles and challenged me to grow. I never felt like my gender mattered. So I assumed when these young women proved they could meet the standard, they would receive the same respect.

On the ground, it sounds like they did. All the Marines from the enlisted infantry course with whom I spoke – officer and enlisted, staff and instructors – agreed the women who graduated met the standard. They conceded they were “good Marines”, that they had proven themselves mentally and physically. There was clear respect for the women who showed up and demonstrated they could do it. When I asked if they would have been confident sending those first women onwards to the fleet, they said they would have, and were reasonably confident the women could have been successful.

On the ground, male Marines felt the decision whether or not to integrate women into ground combat specialties (like the infantry) was a foregone conclusion. They assumed it was a political decision. They viewed the research as something that gave them (the men) time to adjust to having women in previously all-male spaces. They trained the women as if they would be going to infantry units in the fleet, because they felt they had a responsibility to do so.

At the institutional level, the Marine Corps wasn’t ready.

At the institutional level, the Marine Corps wasn’t quite done with Step 4.

The Marine Corps didn’t call it resistance. The Marine Corps called it research. The Marine Corps said the enlisted infantry course tested individual performance, but did not test unit performance. As an institution, the Marine Corps operates in “small units” (usually at the “fire team” level of four Marines). Senior leaders stated the Marine Corps needed to understand the implications of women’s integration not only at the individual level, but also at the small unit level.

There is validity to the idea. Years later, after interviewing a number of male infantry Marines, I gained a deeper understanding of how the infantry actually works. Unlike other specialties, in the infantry, there are three gates a Marine must pass before being considered a “real” infantry Marine.

First, the Marine must pass the infantry course. Second, the Marine must expand upon that training (physical and technical) as part of an infantry unit. Third, the Marine must complete a deployment (with an infantry unit). Only upon successful completion of a deployment would that infantry Marine be considered a “real” infantry Marine.

For its entire history, the Marine Corps assumed any man could succeed in the infantry. There were no restrictions regarding height or weight or any other qualifier. Much later, the Marine Corps would acknowledge,

Research . . . highlighted that the Marine Corps has long relied heavily on the fundamental assumption that simply because a Marine . . . is a male, he should be capable of performing all of the physical tasks associated with the regular duties of that MOS (military occupational specialty). For all intents and purposes, that has been the only physical standard or screen applied to accessing new Marines into physically demanding ground combat . . . specialties.

Brigadier General George W. Smith, Jr. in the United States Marine Corps Assessment of Women in Service Assignments

Of course, this assumption was inherently invalid. At the unit level, Marine leaders had understood this for years. I spoke with infantry leaders who talked about “that one guy in the company (front) office” who couldn’t keep up. Senior leaders spoke of the “bottom ten percent” of male Marines who “never should have graduated” from the enlisted infantry course.

So how well would the women perform? The Marine Corps was determined to find out.

In the weeks following the women’s graduation from the enlisted infantry course, Marine senior leaders initiated a four-week planning session. They brought together ground combat specialists from across the Marine Corps. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to locate documents detailing the planning session’s purpose or composition. Speaking with officers who were part of the planning team, I learned “infantry was never on the table” for integration. The team developed plans for artillery, tanks, and other ground combat specialties, but not for infantry (or reconnaissance).

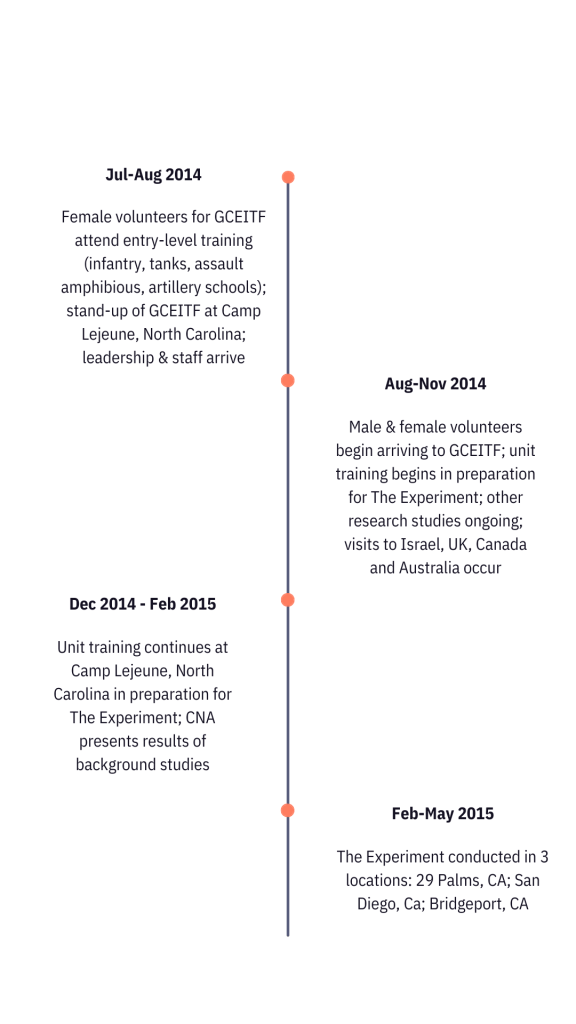

It was here Marine planners developed the original idea to create an entire unit of male and female Marines, across ground combat specialties (infantry, artillery, tanks, assault amphibious vehicles and more) and to test them at the small unit level in an operational environment. It would come to be known as the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force (GCEITF). Those outside the Marine Corps understood it more commonly as “The Experiment”.

This was interesting to me, because the Marine Corps already had an integration plan.

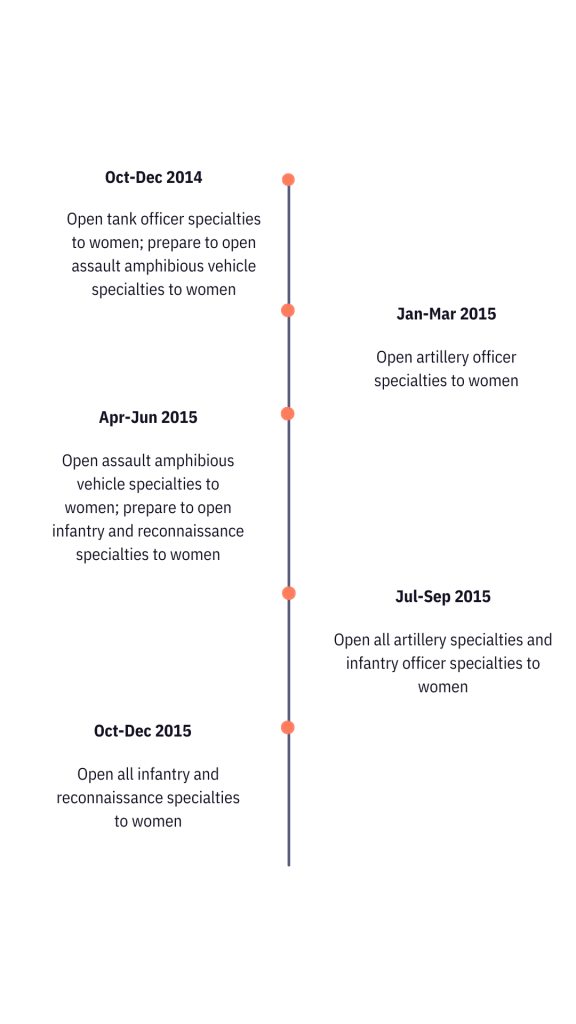

Back in May 2013, Marine Corps and Department of the Navy senior leaders approved a plan which detailed women’s integration into all ground combat specialties (to include the infantry). It outlined the development and validation of gender-neutral physical standards in all ground combat specialities and the development of “a physical screening test . . . by December 2013 that supports the . . . specialty classification process . . . (and would be) implemented prior to the opening of any currently closed . . . specialty”. The plan detailed a sequential opening of ground combat specialties.

Original Plan – May 2013

The Marine Corps’ Training and Education Command had been leading this original plan, which focused on individual performance and individual standards. In an effort to develop the “physical screening test”, they conducted two rounds of testing using male and female Marines, during the summer of 2012.

An internal Marine Corps memo stated the initial rounds of testing “were not helpful”. It didn’t elaborate why, except to say that Training and Education Command would conduct additional testing the following summer. Senior leaders at Training and Education Command were scheduled to brief the Assistant Commandant (the second most senior Marine in the Marine Corps) on the results of this testing in December 2013.

That meeting did take place. The Marine Corps’ approach to gender integration then changed rapidly. Training and Education Command relinquished its role as lead entity. In its place, the Marine Corps established a new office dedicated to gender integration research. Called the Marine Corps Force Innovation Office (MCFIO – we do love our acronyms in the military), I usually referred to us as “the gender office”. It appointed a one star general, (then) Brigadier General George W. Smith, Jr. to lead the office. His first task was to initiate the four-week planning session.

Whatever the Marine Corps decided to do from that point, it needed to move fast. The Defense Secretary had mandated,

Integration of women into newly opened positions and units will occur as expeditiously as possible, considering good order and judicious use of fiscal resources, but must be completed no later than January 1, 2016. Any recommendation (from a service chief) to keep an occupational specialty or unit closed to women must be personally approved first by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and then by the Secretary of Defense; this approval authority may not be delegated. Exceptions must be narrowly tailored, and based on rigorous analysis of factual data regarding the knowledge, skills and abilities needed for the position.

Elimination of the 1994 Direct Ground Combat Definition and Assignment Rule, Secretary of Defense

That was just two years away. That may sound like a lot of time, but the bureaucracy that is the Defense Department, it wasn’t long at all. If one considered the time needed to move through the bureaucratic process of briefing the Marine Commandant (the most senior Marine in the Marine Corps), the Navy Secretary and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, senior leaders had little more than eighteen months. The clock was ticking.

The four-week planning session resulted in a new research plan, which vastly expanded the amount and type of other research projects as part of its overall research effort. It focused on quantitative data and analysis. It included qualitative studies about cohesion and morale, lessons learned from foreign nations, background studies and a massive literature review.

Campaign Plan – February 2014

Approved just two weeks after the planning session concluded, the new Campaign Plan eventually consisted of more than 35 research projects led by more than a dozen different organizations inside and outside the military. The most well known among these was the GCEITF (The Experiment). Consisting of male and female volunteer Marines, it sought,

to evaluate the physical performance of individual Marine volunteers in the execution of individual and collective tasks in an operational environment. The purpose of the experiment was to estimate the effect of gender integration in closed and open . . . specialties, in closed . . . units, and on various measures of readiness and mission success for these . . . specialties (e.g., physical capacity, fatigue, workload, tasks, etc.).

Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force Experimental Assessment Report

At its conclusion, it cost the Marine Corps more than $37 million, diverted 700+ Marines from their primary duties for a full year, and served as the foundation for the Marine Corps’ request to keep infantry units and specialties closed to women. The other research projects cost the Marine Corps additional millions of dollars and hours. This all because a handful of women might want to join the infantry. Why did the Marine Corps go so far? Why did it request to keep infantry specialties and units closed to women? Was it just about physical standards, unit performance and injuries (as the Marine Corps stated)?

At least partly, perhaps. It seems the Marine Corps doubted women’s ability to perform successfully in infantry units. The original campaign plan included a task,

conduct a research study to assess the individual performance of female Marines in the execution of collective tasks in order to determine whether (and which) female Marines are capable of performing the most physically demanding of ground combat tasks.

Marine Corps Force Integration Plan, February 2014

An updated version of the plan replaced that direction with the following,

conduct a research study to assess the physical requirements associated with performing individual and collective tasks for previously closed military occupational specialties (MOSs) . . . and enable research and analysis on individual and unit performance including morale and cohesion, in order to inform Commandant of the Marine Corps decisions on integration of female Marines into previously closed military occupational specialties (MOSs) and units.

Fragmentary Order 1 to Marine Corps Force Integration Plan, February 2014

In the updated tasking, the Marine Corps seemed to touch on the heart of the issue. It included “morale and cohesion”. This was a topic which Marine leaders discussed often. It was obviously important to them, but I was unable to understand what “cohesion and morale” meant to them beyond just having male-only units. Looking back, I think they might have been making the same false assumption they had made with physical standards. I think they might have assumed any male could contribute to “cohesion and morale” simply because he was a male.

Years later, I had an interesting conversation with a male infantry officer. I asked him, if the Marines knew gender integration was a foregone conclusion, why the need for so much research? He response, “it gave us time”, surprised and shined a light. He said infantry Marines needed time to get used to the idea (of women), time to train and work with women prior to making it a permanent change.

People often ask, “what’s the big deal? Don’t these (male) Marines have mothers, sisters, wives, daughters?” Of course they do, but the difference is that they don’t work with any of these women. This matters. The Marine Corps is an intense institution. One kind of needs to be an intense person. Of course, I knew this was not an issue. I’m kind of an intense person, and found myself right at home in the Marine Corps.

But men who had never seen women (boot camp was gender-segregated at the time, so these male infantry Marines literally had not seen a female Marine through all their training and their first units) didn’t necessarily know this. Most of these male Marines did not know what to expect. Could they speak to women in the same manner as they did the men? If not, how would they have to change? How would this change the dynamic in the unit? Could they motivate women the same way as men? Would they be able to perform? What about privacy and hygiene? What about sex and relationships? (the topic almost no senior leader wanted to discuss – but was on all their minds)

How would these men and women work together, socialize together, live together? How would they bond? Would they?

Unwittingly, by creating a unit dedicated to testing women’s performance in a small unit environment (the GCEITF), the Marine Corps also set up a great social experiment. These men and women lived, worked and played together for nearly a year. They would train together, push themselves and each other. They would learn new ways of doing things in their specialties. They would hang out on the weekends, play games in the barracks and get into trouble together. They would learn how to (or whether to) maintain privacy. Some great bonds and friendships developed from the GCEITF. A few marriages later took place. The ripple effect from this unit spread throughout the Marine Corps for years to come.

We learned far more than we ever could have imagined. For some reason, we chose to document only the data. I learned so much more from my interviews with the Marines. It’s so important we capture all that we learned. Future posts will discuss both the research side and the social side. As is usual in the Marine Corps, the Marines on the ground learned (and knew) everything first. Then the institution played catch up.

As a female Marine that was part of the GCEITF, I truly appreciate this article. I have been nervous with the DoD removing DEI related material from its platform, that my unit would be caught up in the mess. So to see private platforms with information on the unit just warms my heart. Thank you.

LikeLike