Ninety percent of a Marine’s problems with equipment can be fixed through proper fit.

Marine Expeditionary Rifle Squad (MERS), 2015

We were halfway through an update. The Smart Adaptations 2 study was a research project I directed, and this was the last brief I organized before departing the Marine Corps Force Innovation Office (MCFIO). I had cajoled and pushed and used every bit of influence I had gained in the previous eighteen months to focus on one thing.

Almost no one agreed with me. They thought the topic not worth studying. Only as we dug into the research did others become convinced.

On a January day in 2016, anyone who had anything to do with infantry training showed up. More than thirty people crowded into a conference room already twice the size of our usual space. As more and more people arrived, I got excited. I knew most of these individuals well. We had spent a lot of time together related to the gender integration research. I knew they had full schedules. I knew they would only attend a brief voluntarily (because coming from me, it was actually an invitation, not an expectation) if they felt it important to be there. Before the brief began, I felt we had already succeeded. When I heard from the senior leader receiving the brief, “ACMC (the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps) needs to see this”, I thought, “YES. We finally got their attention”.

When we enter the Marine Corps, many of us are just worried about surviving the initial training. It was a given that we would get hurt. Many of us simply focused on not getting hurt so badly that it negatively impacted our ability to train. It never occurred to us the equipment we were issued might be a contributing factor. Or if it did, we assumed it was just part of being in the Marine Corps. We often look to ourselves as the weak link – we need to be stronger, more resilient, work harder. Only years later did I begin to question these assumptions.

As part of its extensive list of research projects, the Marine Corps commissioned a study on “Smart Adaptations”. The original idea was to identify adaptations that might potentially facilitate gender integration in ground combat jobs. In February 2015, the team gave its first update to senior Marine leadership. They stated,

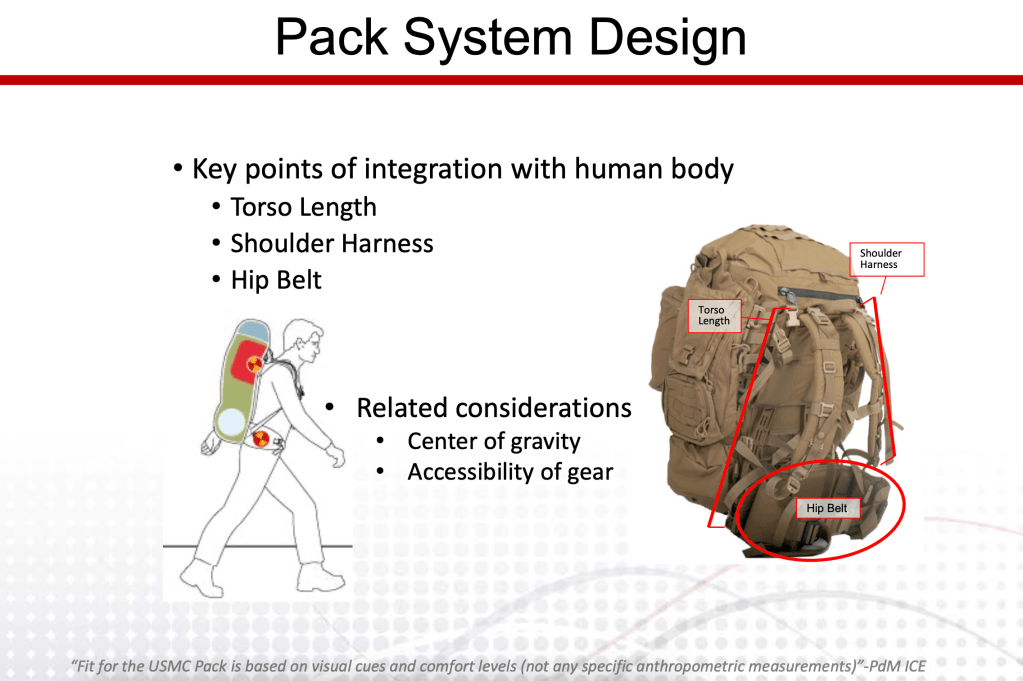

The study team’s approach is founded on the concept that the individual Marine must first be optimized as a “weapon system” in order to maximize performance of physically demanding tasks and integration with major end items. Equipment must be properly designed, fit and configured in order for the individual Marine to operate at his/her potential.

To me, this was revolutionary. And exciting. What if the gear actually fit?

The usual conversations that consider adaptations to hiking revolve around two things: 1) lighter and better fitting body armor and 2) leveraging technology to ease the burden of heavy loads (robots or exoskeletons). Those topics receive ample focus, but are reliant upon more technological development to be fully functional. Those are very cool futuristic ideas, but have not yet made it to the operating forces. I was more interested in what was possible today.

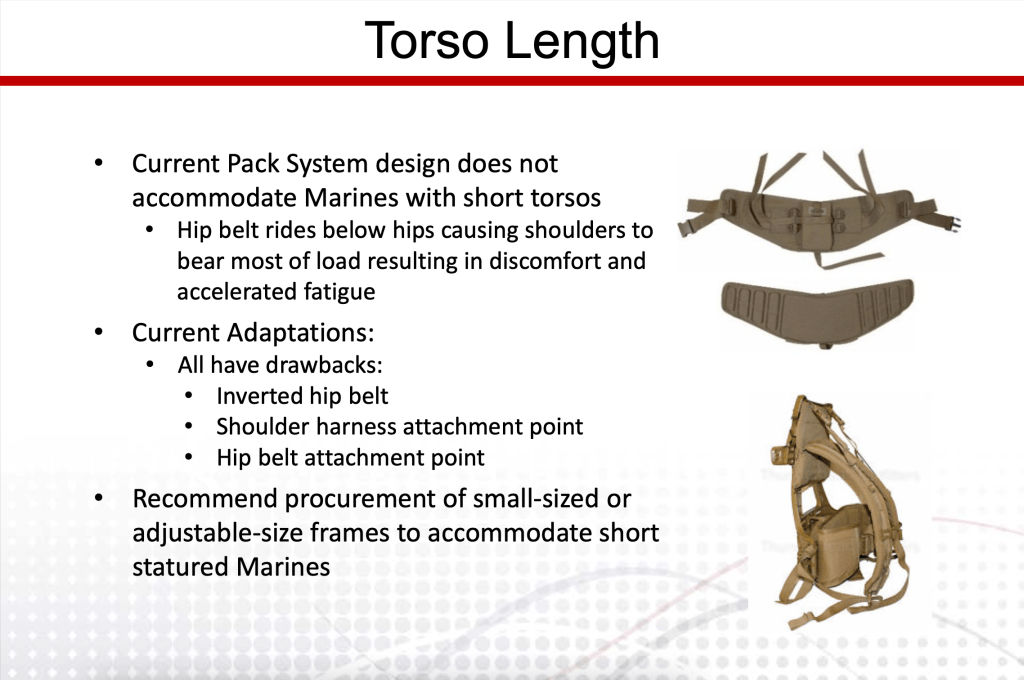

The results of the original Smart Adaptations Study were sufficiently interesting to merit a follow up study. In September 2015, the second study began. This would be my study to direct, and I wanted to research the pack. I disliked the pack more than any other piece of equipment. It never seemed to fit quite right. It was too long on the top (constantly bumping my helmeted head into the top of the frame) and too long on the bottom (the hip belt never actually falling on my hips). Weight constantly pulled from the shoulders, though I had been lectured incessantly about ensuring the weight fell on my hips. Weight shifted as I walked. Surely, something could be done.

The civilian world had already figured this out. There were recreational hiking packs designed for men and women. Why not start there? No need to reinvent the wheel. We reached out to REI, and set up a time to try out packs.

The team at REI was happy to help. Before we began, they measured the length of our torsos. We discovered that most pack systems have adjustable frames (meaning you could adjust them to be shorter or longer, depending on your torso length). We also discovered that the shoulder harness and the hip belt were different on the packs for men and women. REI even had “weight” to add to the packs, so we could get a better sense of how each felt as we walked around the store. We tried on several different packs, for men and women. I had expected to feel a difference, but I was surprised how much of a difference I noticed.

Before we left the store, I was convinced that better fitting packs was critical for all Marines doing any kind of hiking (regardless of gender).

Fit of the USMC pack is based on visual cues and comfort levels (not any specific measurements).

Program Manager, Infantry Combat Equipment, 2015

In my excitement to find a better fitting pack, I almost forgot the current system. It had changed a lot since I last hoisted a pack to my back (for a hike, anyway). I needed to experience the latest pack system for myself. I’m about the average size of a female Marine (5 foot 4 inches tall and 125 pounds), so it seemed a natural next step in the research process.

We coordinated with a contractor working with the Program Manager at Marine Corps Systems Command. The Program Manager is responsible for all aspects of the acquisition process, from identifying requirements (what we want the system to do) to maintenance for the life of the system. Again, this seemed like the place to begin.

Like so many places in the Defense Department, the contractor was a retired Marine. This retired master gunnery sergeant related the challenges he personally saw with the pack. It didn’t really fit any Marine well, partly because the pack was another one-size-fits-all piece of equipment and partly because the new body armor made fitting the pack to any Marine more challenging. He related how he spent his free time – at the Basic Officers Course. When second lieutenants first began their training, he would head over there to help them properly assemble and fit with their packs. He spent his weeknights, often staying there until nine or ten o’clock at night, helping the lieutenants with their gear.

After we spent three hours together in an attempt to make the pack fit comfortably on my body, I understood the challenges. I also understood that no Marine should be expected to perform the kind of adjustments to their packs that this retired Marine was doing for me. These were adjustments he knew from spending his days working with the pack. A new Marine putting together their pack for the first time wouldn’t know any of this. And they shouldn’t have to.

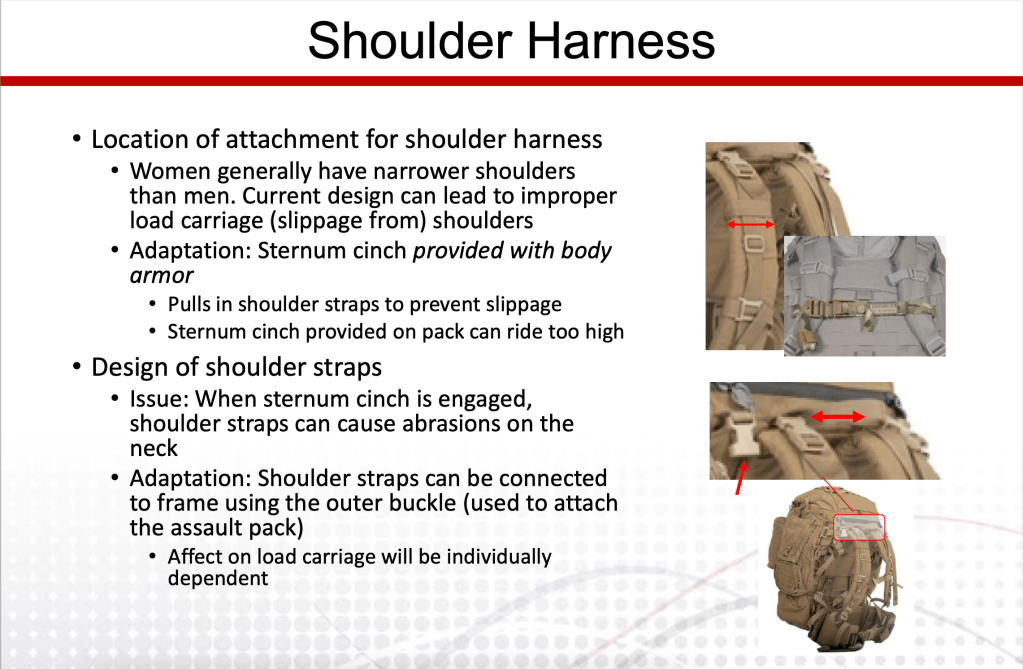

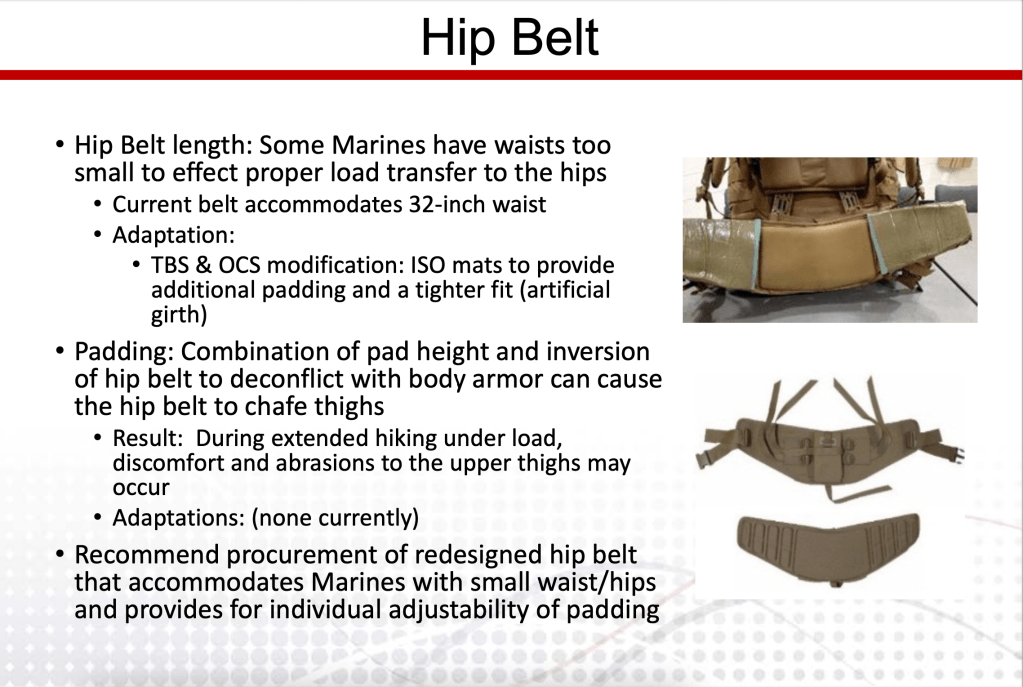

Three things came up consistently, some were gender related and some were not. The shoulder harness did not fit women well. Men’s shoulders tend to be broader than women’s, so the angle of the shoulder harness for a woman should be different than that of a man. Also, the hip belt was too long for smaller Marines. It was designed for a Marine with a 32 inch waist. For many Marines, especially women, they could not tighten the hip belt enough for it to sit properly. Marines would add padding to the waist belt to add artificial girth. They would also invert the hip belt in an effort to make it fit better with the body armor. However, this often caused chafing on the thighs. No solution really worked.

We finally quit after three hours. There was no combination of adjustments the retired Marine could make that helped sufficiently. I could not imagine walking in that pack.

The last item – pack frame length – amazed me the most. In the civilian packs, adjustable frames were built into every pack. Why was the Marine Corps dealing with a frame made for only one size Marine?

The Marine Corps carries significantly heavier loads than any civilian might carry. The REI packs were all internal frame backpacks. Looking at the website recently, I found one pack that looks like it could carry about 65 pounds. External frame backpacks can carry much more. If you read Part 1 of this series, you know the Marine Corps regularly carries loads in excess of 80 or 100 pounds. The internal adjustable frames at REI couldn’t handle the types of loads carried by Marines. But an external frame can.

Adjustable external frames exist, and are on the market today. In 2016, the Program Manager had been seeking to acquire adjustable external frames for the Marine Corps. However, that never happened. When I spoke with the Program Manager recently, I discovered the Marine Corps,

The feedback on our prototypes has been excellent, but unfortunately we have limited funding and cannot procure for every short stature Marine . . . will not be fielding the adjustable component that was being developed a few years ago because of the cost, manufacturability, and maintainability. Instead, we have a low-tech solution – the team created a smaller hip belt and shoulder harness assembly that is going out for solicitation this FY (fiscal year).

Program Manager, Infantry Combat Equipment, 2022

This partially supports the recommendations made six years ago by the research team. Hopefully the Marine Corps will revisit the adjustable frame concept in the future. If maintainability is a reason not to pursue the adjustable pack frame (presumably because the weights carried are so heavy), imagine what that does to a Marine’s back over years of hiking.

In the meantime, is there anything else the Marine Corps could consider? How else could the Marine Corps increase combat effectiveness of its infantry Marines while maintaining the heavy loads it carries? There is one more thing. It might seem unconventional to some, but on greater reflection (I believe) just makes sense. And I didn’t come up with this idea. The Royal Marines thought of it long before we did. In my next (and final, I promise) post on Hiking Under Load, we’ll dive deeper into what we learned on our trip to the United Kingdom and how the Marine Corps might apply it to its force.

Thanks ??

Get Outlook til Android ________________________________

LikeLike