When I asked the GCEITF’s Gunner, CWO5 Nick Vitale, the role of leadership in cohesion and morale, he said, “it’s the hinge!”. Somehow everything always comes down to leadership. It’s the lynchpin to so many things.

Cohesion and morale – the military always unites the concepts – is incredibly important to unit performance. But it’s not something usually measured. Before the GCEITF, as far as we know, there was no historical data on cohesion and morale. For good reason. It’s really hard to measure something so amorphous.

The Marine Corps dedicated significant resources in terms of time, money and brain power during the research period to cohesion and morale. The Marine Corps took a guiding principle regarding cohesion and morale from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and incorporated it into several research projects: “Ensure the success of our Nation’s warfighting forces by preserving unit readiness, cohesion and morale”.

Various surveys queried Marines on cohesion – within the very unit designed specifically to control for cohesion (the GCEITF). It also faced numerous challenges to morale – all for excellent scientific, administrative and logistical reasons.

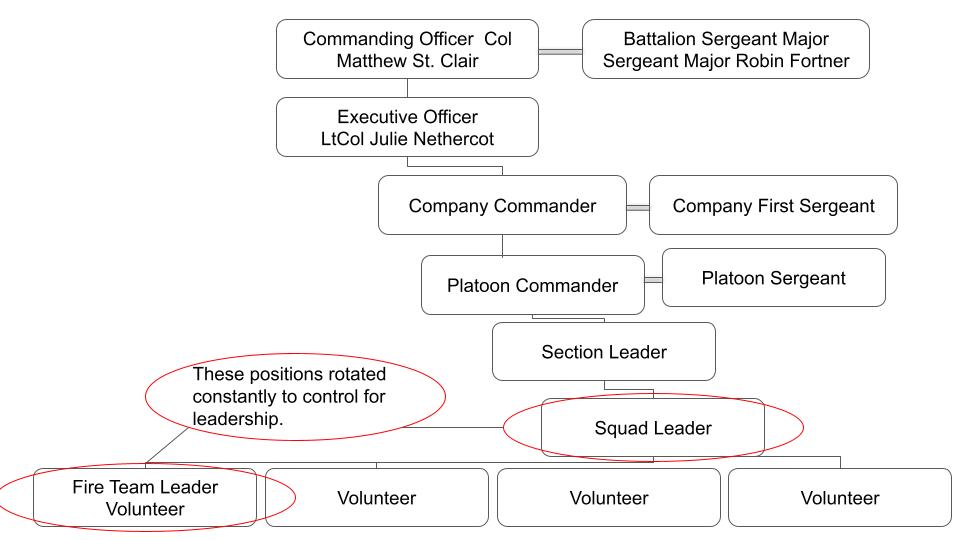

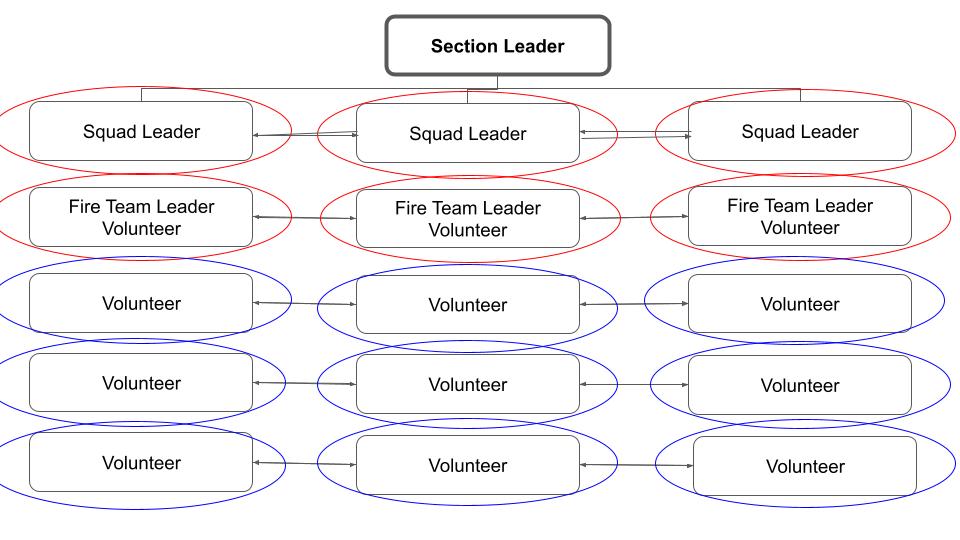

The Experiment planned to shift Marines amongst their small unit teams constantly to control for the leadership variable (and the cohesion variable). The idea was, if no one had consistent leadership, then no team could disproportionately benefit from good leadership. Conversely, no one could disproportionately suffer from poor leadership (and thus skew results).

Upon reflection, conducting surveys about cohesion in a unit designed to control for cohesion seemed moderately ludicrous.

Or was it? You see, much like leadership, cohesion and morale are simply necessary aspects of any successful unit. The GCEITF itself would not have been successful if it did not have cohesion and morale. So how can a unit simultaneously control for cohesion yet have it? And, if it was possible, how did they do it?

Before going further, let’s define terms.

Cohesion defined: “the action or fact of forming a united whole”.

At its heart, cohesion is trust. Trust everyone on the team is united around the same goals, trust that everyone on the team can and will contribute to those goals, trust that everyone will work, sacrifice and even suffer to attain those goals. Have you ever played on a sports team, or even done a group project for school? Then you understand cohesion (or lack thereof).

Morale defined: “the confidence, enthusiasm, and discipline of a person or group at a particular time”.

Confidence. Enthusiasm. Discipline.

Those are three very different but powerful words. Confidence in the unit’s ability to accomplish the mission. Enthusiasm for the unit to accomplish the mission. Discipline for the unit to accomplish the mission. Create morale.

As I did the research for this post, I reflected how odd it was that nowhere in the research – either civilian or military – did it state the integral connection to leadership. I wondered how cohesion or morale could possibly exist in leadership vacuum. It was possible, but certainly more challenging.

We knew intrinsically how important leadership was to cohesion and morale. Remember, leadership is like air to Marines. We don’t need to mention it because we all accept it as a natural part of our environment.

We do plan for it.

The Experiment was designed to rotate leadership at the small unit level. But leadership at higher levels (platoon, company and battalion) remained constant. This was the critical piece to success. The Marine Corps stacked the deck, as much as it possibly could.

It chose more senior people, and usually more experienced people than usual for a battalion-sized unit. Rather than a lieutenant colonel, the GCEITF commanding officer (CO) was a full colonel. Rather than a major as an executive officer (XO), the GCEITF had a lieutenant colonel.

Colonel St. Clair had just commanded a Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU). This meant he had deployed overseas leading a unit of approximately 2,200 Marines and Sailors, men and women, with the full range of Marine Corps ground, aviation, logistics and command and control capabilities. He could certainly lead a unit of approximately 700 Marines, of similar structure and training requirements, and his previous experience as a commanding officer equipped him well to address the other challenges the GCEITF faced.

Colonel St. Clair’s right hand person, Sergeant Major Robin Fortner, had previously served as a battalion sergeant major twice – at 4th Recruit Training Battalion (previously all-female) at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island and at 2nd Law Enforcement Battalion.

Colonel St. Clair’s Executive Officer, (then) Lieutenant Colonel Julie Nethercot, had previously served as the commanding officer of 9th Communications Battalion when it deployed to Afghanistan.

The list goes on and on. The Operations Officer had served as an Operations Officer twice before – in an infantry battalion, and at the enlisted infantry school when the first women came through. The Gunner had nearly thirty years of infantry experience under his belt. The company commanders and first sergeants had led those types of units before, often on an overseas deployment.

As much as Marine senior leaders were able to pick and choose, they did. The GCEITF needed every bit of excellent leadership it could get, because it faced challenges few other Marine Corps units did.

First, the GCEITF was starting from scratch. They built the unit from the ground up. Conversely, most units are standing units. They have existed for years or decades or more. They have histories and infrastructure. Individuals rotate in and out, but the unit itself remains. Incorporating “new joins” takes time and effort, but it’s known and happens automatically. Learning strengths and weaknesses of new members takes time. Most of the people remain constant during any given “turnover” period and thus the ship (unit) keeps moving forward.

The GCEITF had to do this all at once. Everyone was new. Some of the leadership knew each other, at least by reputation if not personally. Most of the Marines did not know each other. They had to learn each other; the women had to learn their specialties; they had to train for the Experiment; they had to build the unit, and learn how to get along with each other.

No matter how excellent the leadership or the Marines, there are going to be bumps and jolts along the way. I know because I did this, with a different unit, in Afghanistan.2 There’s nothing quite like standing up a unit from scratch. It can be mind-numbingly exhausting. Frustrating. The pace is dizzying. It requires every ounce of strength, attention and commitment a person possesses. It requires experience, maturity, a level head and commitment to the mission.

Add to that – all of the Marines participating in the Experiment itself were volunteers. Because the Experiment was human subjects research, the Marines had to volunteer and sign waivers to participate. That meant they could also leave whenever they wanted.

This is anathema in the Marine Corps, and took a lot of getting used to by everyone. This option to leave would come into play over and over again, as Marines decided they didn’t want to do this anymore and would leave.

The rest of the Marines were staff (or “voluntolds”). They were there for the duration, whether they wanted to be or not.

Second, the GCEITF had a somewhat unique mission. The Marine Corps based the GCEITF on a battalion landing team (BLT) structure. The BLT unit constitutes the ground combat element of a Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU). So the Marine Corps, and the Marines within the GCEITF, knew what that looked like, how it functioned, its purpose, etc. This helped a lot.

The difference lay in its purpose. The Marine Corps never intended to deploy the GCEITF. It existed solely for the purposes of research. Not all the Marines understood the intricacies of the Experiment, often until they started doing it.

Third, the unit put women and men together in ground combat roles for the first time. There was the logistics of women and men living together and working together, of keeping a close eye on any romantic involvement. There was also the most basic question – which spoke directly to the cohesion and morale question – how would the men feel about the women? How would they treat them? Would they accept them? More than that, would they teach them and train them?

There was one more thing unique to the GCEITF.

It was a nonstop “dog and pony show”. The Marine Corps was doing something no other service had ever done. It put men and women together in a battalion-sized ground combat unit to test how they performed. Everyone wanted to see it. Congressmen. Defense Department officials. Marine senior leaders. Other service senior leaders. International military leaders. The press . . . the press . . . the press. It was a constant in their lives.

GCEITF leadership – men and women united – focused on two major items as they worked to create cohesion and morale. They knew at the small unit level the Experiment had the Marines moving around constantly, to control for both leadership and cohesion. But at the higher levels, leadership and teams remained constant. The below offers a generalized pictorial view of this.

GCEITF leadership understood clearly the challenges they faced. Colonel St. Clair and SgtMaj Fortner walked around. A lot. If you’ve never heard the phrase, “leadership by walking around”, it’s a powerful tool. Visibility and presence can be a powerful leadership tool. During my interviews, Marines talked about Colonel St. Clair and SgtMaj Fortner over and over again. They talked about how visible they both were – together and individually. They talked to the Marines, checked on the Marines, interacted with the Marines. The two remained united in their vision for the unit, for how they expected their Marines to act and treat each other – as Marines and as professionals. There would be no special treatment, or disregard, for any Marine – regardless of gender. This set the tone for the entire unit. Colonel St. Clair said it,

This is a family. Family, I used that word EVERY DAY. And when you use it, and then you demonstrate it, it takes hold . . . We are family, we’re in this thing together. Every family has its internal squabbles, and we’re gonna have those, but we’ll deal with those as a family. And when we need outside help, we’ll ask for it. But it was part of that reinforcement of ‘hey, we’re family’.

Colonel Matthew St. Clair, CO of the GCEITF

Colonel St. Clair and SgtMaj Fortner also understood the importance of creating a unit outside the microscope of the “dog and pony show” – outside the research team or anyone else. One thing Marines brought up numerous times in interviews was Colonel St. Clair’s bagpipes. They all remembered the bagpipes and said, “you’ve got to get Colonel St. Clair to talk about the bagpipes”. He started learning the bagpipes several years previous to the GCEITF, and he used it as a connection point and opportunity for decompression and levity with the Marines. He’d play in the morning, before physical training (PT). He’d play in the evening, as the Marines were settling down to rest.

At the end of the day, (it was) just to inject something completely different into the environment . . . The Marines are just busting their hump all day, in the heat. It’s Groundhog Day, every day, because of the repetition of what we had to do for each of the tasks and all the visitors we had. When I was playing, I think Marines felt like it was just us, it was just the GCEITF. Everybody else was gone for the day. And this is our environment. That was I think . . . (w)hat I contributed by playing the pipes. It made for a good place for them (the Marines) to be at the end of the day.

Colonel Matthew St. Clair, CO of the GCEITF

Second, leadership set the standard that they were all Marines first, that they were there to do a job, the standard for men and women was the same, and they would be professionals about it.

One of the things that surprised me most was discovering that some of the enlisted male Marines would help the enlisted female Marines. One of the male enlisted leaders shared with me that male Marines would help female Marines carry their pack, lift something heavy or otherwise do something you and I might think of as chivalrous. This was definitely unique to the enlisted side. Officers never did this. Male officers never had any problem allowing female officers to lift, carry or do anything all on their own. I laughed when I remembered my initial training. We were all the same, as far as I could tell. Definitely no special treatment for any of us.

Senior enlisted leadership squashed the males’ chivalric conduct quickly. Everyone became just another Marine. The women carried the same packs, the same weapon systems, ran the same number of miles and did pull-ups alongside the men. As they proved they were there to work and that they were serious, the men saw this and respected it. They became part of the team.

This may not have been universal amongst all the units in the GCEITF. Certainly, there were variations amongst the companies and sections. But this is generally what I’ve heard – the women began proving themselves – as much in performance as in grit, resilience and determination. They started proving they were serious and that they could hang with the guys, on and off duty.

It seemed the harder they worked, the tougher the conditions, the tighter the cohesion. The Marines from Weapons Company seemed to have the fondest memories of the most miserable times. They admitted their leadership pushed them hard, but they understood why and appreciated it once they got out to Twentynine Palms.

The GCEITF accomplished something special that few others seemed to notice. They led a disparate group of Marines who had never met each other to become a family in an extraordinarily short amount of time. They fostered cohesion and morale at the platoon, company and battalion level so when the Marines moved around at the squad and fire team level, it didn’t matter.

The Operations Officer, (then) Major Larry Lowman said it best when he said, “The GCEITF was a great leadership experiment”. Marines re-enlisted in the Marine Corps because of the GCEITF. Some Marines got married (some then got divorced). Some Marines remember the GCEITF as their favorite time in the Marine Corps. Out in the civilian world, Marines are known for leadership. This is why.

FOOTNOTES

1“Ensure the success of our Nation’s warfighting forces by preserving unit readiness, cohesion and morale” from the Women in Service Implementation Plan, 9 January 2013.

2During 2013, I deployed to Afghanistan with the R4OG (Redeployment and Retrograde in support of Reset and Reconstitution Operations Group) as a company commander. The unit brought together Marines from all three active duty Marine bases (in North Carolina, California and Okinawa) along with fourteen different reserve units. Its mission was to gather, clean, pack and ship all Marine Corps ground equipment back to the United States for repair and redistribution. The Marine Corps created it specifically for this one function. It only ever existed in Afghanistan.

One might consider that morale and cohesion are subjective terms and therefore their status within a unit is based on an individual’s perspective. One Marine may think morale and cohesion are outstanding and another Marine standing next to them may think just the opposite. Tough to measure, but Marines certainly know when morale and cohesion are inadequately present.

LikeLike

Ok but if you do any pictures for the book, you have to find one of Col St Clare with the bagpipes and matching desert digi-cam *utilikilt*. That’s the only way to get the full effect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Noted! Will do.

LikeLike